There are a few things everyone knows about redistricting. It happens every 10 years to reflect changes in population. There is a concept called one person, one vote, which basically means every district must have roughly the same number of people in it. And it is a politically-charged process that tends to pit different groups against each other in order to gain an advantage.

In Louisiana, lawmakers drew new districts for Congress, the Legislature, BESE, and the Public Service Commission. It happened against this backdrop.

The state’s population grew slightly – about 2.74% – but more importantly it shifted south, away from north Louisiana, out or rural areas, and into more urban and suburban communities. There was also a shift in demographics. The White population declined by about 179,000 people, or 6.3%. The Black population grew by about 56,000 or 3.8%. And the population of other races grew by about 247,000. Louisiana became slightly less White and somewhat more diverse.

There are a number of widely-accepted principles that states can and do use to draw district lines and a handful of legal requirements dictated by federal law. In Louisiana’s redistricting session, Republicans relied heavily on the allowable principle of preserving existing district alignments when drawing new districts. Democrats sought to redraw districts based on their interpretation of federal law, specifically Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Section 2 prohibits plans that intentionally or inadvertently discriminate on the basis of race, which could dilute minority voting strength. They further leaned on a Supreme Court decision from 1986 that established three criteria for demonstrating minority votes were being diluted:

- The minority group must show that it is large and compact enough to make up a majority in a district.

- The group is politically cohesive or tends to vote much the same way.

- And it must show that White voters vote in such a bloc that they will usually defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.

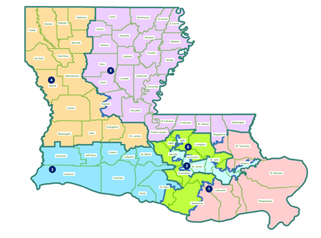

In many ways, that was what the session was all about. For simplicity we’ll focus on the maps for new Congressional districts, but the same issues were largely in play for the other districts, as well. Republicans configured districts that largely mirrored the existing Congressional map. While they had to account for the population shifts, a side-by-side look at the maps shows most of the changes were around the margins and the redrawn districts look much like the older ones.

There was also very little change in the demographics of the districts, with adjustments in racial makeup being limited to 3% or less. Republicans pointed out that they were largely preserving district boundaries that had been in place for a decade and had been approved by the U.S. Justice Department.

Democrats countered with the argument that over that decade the state’s racial mix had changed. White population declined while the number of Black residents grew and that justified new maps that would create a second majority-minority district to go along with the existing district that runs from New Orleans to parts of north Baton Rouge.

They pointed out that the current single majority-minority district represented 16% of the six Congressional districts while adding a second district would bring the districts into line with the Black population of the state which is one-third of Louisiana residents. They introduced more than a dozen bills with a variety of map configurations to try to achieve that.

Republicans rejected all of them arguing that federal law and U.S. Supreme Court rulings do not require districts to reflect the racial makeup of the population and states can use a number of other criteria to legally redraw districts and remain in compliance with the law.

So, when the session ended on Friday, the number of majority-minority districts remained unchanged and Republicans, who have a strong majority in the Legislature, prevailed in passing their preferred maps for every office. The question now is whether Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards will veto any of the maps, as he suggested he might if the Congressional districts did not allow for greater minority representation.

Right now, that’s unclear. The Congressional maps did not pass by a veto-proof supermajority in the House. A handful of Republicans voted against the plan, but their concerns were more about changes in district boundaries close to their communities and not about the bigger issue of more minority representation.

What is certain is that Democrats and other public interest groups will challenge the new maps in court. Much of the testimony they presented in committees had the feel of laying an evidentiary foundation for a judicial test, but there are big questions about whether they can prevail.

The U.S. Supreme Court recently allowed Congressional districts in Alabama to stand – at least for now –overturning a lower court decision that found the maps violated the Voting Rights Act. While the justices did not rule on the merits of the case, court watchers see the Supreme Court’s decision to postpone action in Alabama as a signal that they are more willing to defer to the will of state legislatures on redistricting decisions.

All that said, the session is over, the maps have been redrawn, and the controversies of the last few weeks will continue, either through a veto battle in the Legislature or a legal fight in the courts.

Though it was a difficult and painful session for many, sights now turn to the regular session which gets underway in March. There is still a lot of important work for the Legislature to do for the people of Louisiana, not the least of which involves making wise and forward-looking investments of huge amounts of federal money available because of the COVID pandemic.

It is CABL’s hope that the political bumps and bruises of the past few weeks can be set aside, and lawmakers are able to come together and deliver outcomes that will benefit all of the people of Louisiana. Given the political rancor we see in other places around the country, that would send a positive message that should be welcomed by all.